Keep a lookout for other aircraft – |

|

Oh, trust me, there’s a good story behind this photo! We’ll get to that. First, let’s take a quick trip back to the very beginning of your flight training, back to when you were first encouraged to “see and avoid” other aircraft. That mantra will be true for all of your flying days. In fact, what surprises a lot of people when they begin instrument training is that pilots flying on IFR flights are required to see and avoid other aircraft too! Check out what it says in the FARs: “When weather conditions permit, regardless of whether an operation is conducted under instrument flight rules or visual flight rules, vigilance shall be maintained by each person operating an aircraft so as to see and avoid other aircraft…” 14 CFR §91.113(b)While operating VFR, you must always fly so that weather conditions permit you to see and avoid other aircraft! That is the reason for the VFR cloud clearance and visibility requirements in the FARs, see “Basic VFR weather minimums” 14 CFR §91.155 for a refresher. Pilots are further required to not create a collision hazard by operating too close to another aircraft 14 CFR §91.111 and then there’s the FAA’s catch-all rule which prohibits a person from operating in a careless or reckless manner 14 CFR 91.13. Of course, none of this will matter if a pilot isn’t vigilant to begin with and goes off and collides with another aircraft. Then the rules just end up being the list of things they did wrong! |

|

How often do you check your blind spots? |

|

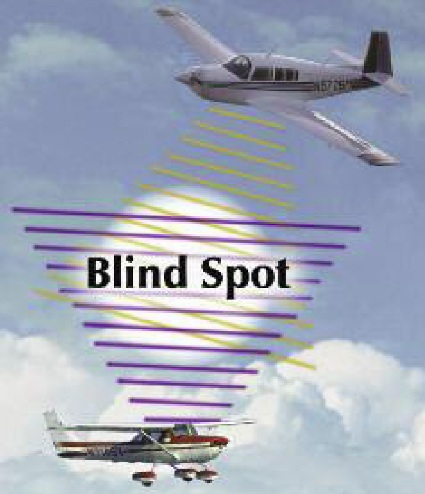

Well great, you’re probably diligent about watching out the windows of your airplane and looking for other traffic. That’s only a part of your duty. You’ve also got to see what’s in your airplane’s blind spots. Every airplane has them! Pilots of high wing airplanes have a lot of difficulty seeing aircraft that are behind them when the other aircraft is at the same altitude and above. Even aircraft in the 9 to 10 o’clock positions can be hard to see when flying a high wing airplane. Low wing pilots have trouble seeing aircraft below them from about the 8 o’clock to 10 o’clock positions when the opposing traffic is in close proximity. Every airplane pilot has a lot of trouble seeing an aircraft below and in front of them. The nose of an airplane can obstruct visibility for a long distance ahead of you (see the article below). So what is the vigilant pilot to do? The answer is to maneuver regularly so that you can check your blind spots! |

|

Watch your blind spots when you climb. |

High wing and low wing

Courtesy: AOPA Air Safety Foundation |

When airplanes climb, the nose obstructs visibility even more dramatically than it does in level flight. Yet, the Airplane Flying Handbook reminds us that: “Proper scanning techniques are essential to a safe takeoff and climb, not only for maintaining attitude and direction, but also for collision avoidance in the airport area.” Page 5-4 Airplane Flying Handbook (2004).To accomplish this, the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) recommends that pilots “execute gentle banks, left and right at a frequency which permits continuous visual scanning of the airspace about them.” At 4-4-15(b) AIM (2010). Another good technique is to lower the nose slightly at frequent intervals during the climb. Many pilots feel that they must continue a best rate of climb (VY) pitch attitude for the entire climb to altitude. This is sometimes such a high pitch attitude that you cannot effectively scan for traffic. An additional consideration is that an excessive pitch attitude can lead to higher engine operating temperatures due to reduced airflow through the cowl. Therefore once you are above pattern altitude, it is advisable to climb with a slightly reduced pitch attitude, resulting in a slightly higher airspeed than VY, in order to improve cooling and to increase forward visibility. If there are times when a best rate of climb pitch attitude is required for a prolonged time, the performance lost to momentarily lowering the nose to check for traffic is nothing compared to the degradation in performance from colliding with another aircraft during your climb! |

|

Watch your blind spots when you climb - even at towered airports! |

|

Certainly, at non-towered airports pilots must be alert for other traffic. But don't forget, at towered airports, pilots must scan for other aircraft in and around the pattern with them too. Remember, it is NOT the function of the control tower to provide separation services, and they don’t! This isn’t to say that a control tower, on a workload permitting basis, won’t call traffic to you. They will. After all, they’re no more interested in watching a midair collision than we are in having one! But, it’s the pilot’s responsibility to see and avoid, not the controller’s responsibility to tell us to look out and swerve! |

|

Clear your blind spots before you turn. |

|

Among the first tasks that students should learn is “straight and level” flight. However, too few students learn to do this by looking to the sides of the airplane to ensure that the wings are neither too high nor too low. If one wing is higher than the other, the airplane will not fly “straight”! The Airplane Flying Handbook confirms this technique: “Straight flight is accomplished by visually checking the relationship of the airplane’s wingtips with the horizon. Both wingtips should be equidistant above or below the horizon (depending on whether the airplane is a high-wing or a low-wing type)…” Page 3-5 Airplane Flying Handbook (2004).The added benefit is that by becoming comfortable in the initial stages of training with looking to the sides, pilots develop an essential habit of scanning effectively for traffic! When an airplane is turned, pilots must clear the area in the direction of the turn. If you’re flying a high wing plane, you must learn to lift the wing on the side to which you intend to turn before you begin to bank in the direction of the turn. If you’re flying a low wing airplane, the process is more intuitive, but remember that there could be an aircraft that was shielded by your wing or fuselage that you’ll be surprised to find as the turn progresses. |

|

Look around while you’re in cruise flight. |

|

It’s very easy for pilots to get focused on what’s ahead of them while in cruise flight. There are checkpoints to watch for, nav logs, and navigation equipment to monitor, plus, your destination is in front of you. However, the traffic sharing the sky with you is all around you! You should be attentive to the airspace to your sides, above and below to ensure that you and another aircraft are not converging. Head on collisions are unlikely because most pilots spend the majority of their time looking forward. Moving your head isn't sufficient because of the blind spots every airplane has, and just because your airplane’s heading could remain constant during long portions of a flight doesn’t mean that pilots shouldn’t alter course regularly to check for traffic. Note: “Sustained periods of straight and level flight in conditions which permit visual detection of other traffic should be broken at intervals with appropriate clearing procedures to provide effective visual scanning.” See 4-4-15(c) AIM (2010).Of course, this quote applies equally to VFR and to IFR flights! So, even if you’ve got an autopilot engaged, and you’re conducting an instrument flight, or navigating VFR with a GPS, it’s worth it to turn slightly in order to clear the skies around you from time to time. |

|

Avoiding surprises means knowing where to look. |

|

Accidents and incidents regrettably do happen, often with tragic results. They’re disturbingly frequent around airports and in the airport pattern where there is a higher traffic density. So, pilots need to use the clearing procedures discussed above. Further, while good listening and communicationg skills help to sort out who is around you and where they are, you can’t solely rely on the radio because at non-towered airports there can be people operating legally without radios, or foolhardily ignoring their radios. Here is a local case where things broke down in several ways:

Granted, no pilot should have attempted to land over another aircraft. But if the pilot of the Cessna, which was equipped with radios, had made any announcements it could have broken a link in the accident chain. |

|

Now, back to the photo that began this article. Here is another taken from a different angle. This reportedly occurred in Florida, in December 1999 at the Plant City Municipal Airport. Apparently, the pilot of the Piper was in the pattern and didn’t realize that there were 2 Cessnas preceding him to the airport. He saw the first land, and collided with the second on final. The collision caused the 2 airplanes to lock together and descend as one! The pilot of the Piper claims not to have known of the collision until he didn’t end up as low to the ground as he’d expected. Apparently, the occupants of the Cessna were very much aware of the Piper’s presence and landed as uneventfully as possible, choosing the grass adjacent to the runway to soften the impact! There were no injuries, and both airplanes flew again. |

|

Don’t become the next statistic! |

|

I wouldn’t expect to be as lucky as the people in the second group described above. So what’s a pilot to do? The answer isn’t just “look”. It’s about knowing where and knowing how to look.

|

|

Article by: Terry Keller Jr. |

|