Could you be about to carry |

Photo by Steven W. Ells |

Each year, well-wintered pilots everywhere, especially where I instruct in the Northeast eagerly look forward to flying, and preflighting, in more moderate temperatures as spring approaches! But, we would do well to remember that pilots aren’t the only creatures anticipating taking flight on pleasant spring weather days. Migratory birds will have begun their return, and they’ll be looking for a spot to call home for the summer. There are several parts of your airplane that could be high on the list of desired locations, and you’ll need to check them especially carefully! |

Why are there birds on my engine? |

Many species of birds seek out cavities in trees in which they build nests. Bird houses simulate a tree cavity, so people supply them to attract birds to their property. Unfortunately, airplane engine cowls also make a fine substitute for a hollowed out tree trunk – to a bird at least. Nests provide protection from predators and the elements and are insulation for the birds. It is the insulating quality of the nests that make them so problematic for pilots when they are built on airplane engines. |

You probably have an air cooled engine! |

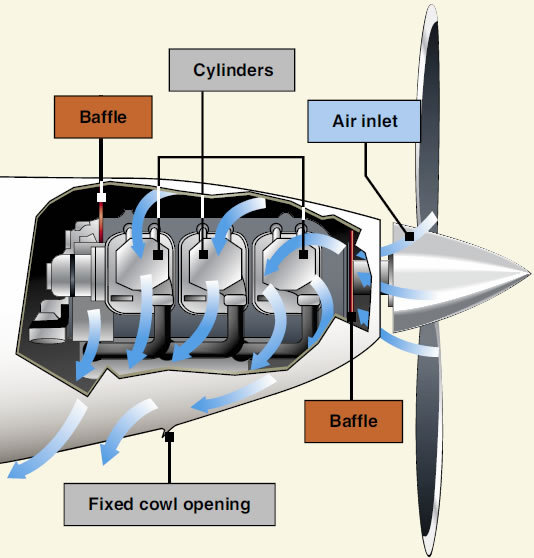

Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge Figure 6-19 Most general aviation airplanes have air cooled engines. “Air cooling is accomplished by air flowing into the engine compartment through openings in front of the engine cowling. Baffles route this air over fins attached to the engine cylinders…where the air absorbs the engine heat.” Page 6-16 Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge 2008 The “fins” on the cylinder are heat sinks. The fins dramatically increase the surface area of the cylinder. The larger surface area makes cooling the cylinders more efficient. When the airflow into the cowling is disrupted, engine temperatures increase. For example, prolonged climbs do not allow for the normal efficient airflow through the engine cowl because there isn’t as direct a flow of air into the cowling. This is why pilots must be especially diligent about monitoring engine temperatures throughout the climb, especially during the summer. High engine temperatures would also result from some character coming along and spreading some sort of insulation all over your engine’s cylinders – a bird perhaps! Remember, nesting materials provide insulation to birds, so the nest will not only disrupt the airflow that cools the engine, but it will also prevent the cooling fins from doing their job of dissipating heat. |

Engines are very hot to begin with, but… |

The Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge reminds us that “Operating the engine at higher than its designed temperature can cause loss of power, excessive oil consumption, and detonation. It will also lead to serious permanent damage, such as scoring the cylinder walls, damaging the pistons and rings, and burning and warping the valves.” Page 6-17. The implication is that an airplane flown with a bird nest in the cowl may be very detrimental to the engine. The engine will not be able to cool properly, so damage is likely. If a nest is found, it must be removed to avoid an excessive buildup of heat. Further, birds just can’t be counted on to build nests out of FAA approved flame retardant materials, so if a nest is discovered, you must ensure that it is completely removed to avoid an engine compartment fire! |

So what do I look for? |

As you see in the photo at the top of this page, many aircraft have engine cowls that open to provide an easy means to visually inspect the engine compartment. However, many more aircraft do not! Pilots must be conscientious during preflight inspections to thoroughly check air intakes and look on top of the cylinders for signs of nesting activities. Fortunately, twigs and grass aren’t the only signs that you’ve got birds. Check the prop and spinner, external cowling, and the ground for signs of bird droppings. If you find them, it’s very likely that birds have been spending a lot of time around your plane! While it is imperative that pilots ensure that there are no birds or other creatures nesting in the engine compartment, the cowling isn’t the only part of an airplane that critters will be attracted to! Airplane control surfaces have points of attachment that provide easy access to would-be nest builders. Mechanics often find nests in wings, aft portions of the fuselage, wheel wells in retractable gear airplanes, and in empennages of airplanes. Be certain that you are always on the lookout for tell-tale signs of animals making a home within your airplane. You will likely see droppings on control surfaces and on the ground around the plane, and you should look for fur, feathers or bits of grass or twigs at easy access points when you are checking the flight control surfaces. |

An ounce of prevention... |

Many airplane owners use cowl plugs and foam to block various openings around their airplane, but don’t become complacent just because you use them. Engine cowls have an obvious opening directly behind the propeller, but that’s not the only passageway into the engine compartment. Animals can gain entry around the exhaust, and through the openings at the bottom of the cowl where the landing gear is mounted and cooling vents open. No airplane can be completely sealed off to a motivated nester! And while we’re on the topic of protecting airplanes from nest builders, don’t think that a hanger is protection either. Small birds and rodents can get through amazingly small openings. Most hangers don’t offer complete protection from animals seeking shelter. Always preflight thoroughly, and in the spring and summer, be especially aware of the possibility of stowaways in your plane. |

Article by: Terry Keller Jr. |

|